A Sample of Tax Cases in Federal District Court: Criminal vs. Civil

-

Eddie R. Mendoza

Eddie R. Mendoza

View Bio

Introduction

Most federal tax disputes are resolved administratively or in the United States Tax Court, where taxpayers might challenge IRS determinations in a specialized forum that requires no prepayment of the disputed tax. But not all tax cases follow that path. Many land in the United States District Courts—either because the government initiates a lawsuit to enforce federal tax laws or because a taxpayer seeks redress after paying a tax. And in criminal matters, District Court is the only venue available—the exclusive forum in which the government may prosecute tax-related offenses under the federal law. District Court tax litigation, whether civil or criminal, differs significantly in form, procedure, and consequence. This blog post outlines common categories of both civil and criminal tax matters in District Court and concludes with a comparative overview of the two paths.

A. Civil Tax Matters in District Court

Civil tax litigation in District Court falls into two basic categories: suits filed by the government against taxpayers and those brought by taxpayers against the United States. These matters may generally concern the enforcement or refund of tax obligations, the priority of tax liens, or compliance with IRS administrative tools like summonses, among other types of suits. A non-exhaustive sample of these cases includes:

• Collection Actions.

The government might file suit to reduce a tax assessment to judgment, often as a precursor to enhanced collection efforts. The resulting judgment may allow the government to enforce statutory federal tax liens or levy assets more broadly. In these actions, the taxpayer may dispute liability—for instance, by contesting responsibility for unpaid payroll taxes under the Trust Fund Recovery Penalty and arguing they were not a “responsible person,” or that any failure to remit the payroll taxes was not “willful.” If the government prevails in this type of suit, the court will enter a “judgment” reflecting the amount owed by the taxpayer, which the government might then use to further any efforts to collect the tax owed by the taxpayer.

• Lien Enforcement.

By statute, a federal tax lien generally attaches to a taxpayer’s property upon the assessment of a federal tax. When a federal tax lien attaches to property, the government may file a civil action to enforce the tax lien and, in some cases, to foreclose on the property. The property at issue may include real estate, retirement accounts, or other personal assets. These cases often involve allegations of fraudulent transfer, nominee ownership, or alter ego liability. For instance, the government might argue that its federal tax lien attaches to property owned in title by a third party because the taxpayer transferred the property to that third party in a fraudulent manner, such as to avoid collection or assessment of tax by the IRS. Such “transfer” cases are often fact intensive. The government may also seek appointment of a receiver to manage or sell the property at issue to help pay off the tax liabilities. The government often brings a collection action and a lien enforcement suit together in a single suit.

• Injunction Actions.

To prevent ongoing alleged violations of tax law, the Department of Justice may seek an injunction against a taxpayer or third party, such as a return preparer accused of fabricating returns or a business “pyramiding” employment taxes. For instance, the government might allege that a return preparer has systemically prepared falsified tax returns for customers thereby causing tax harm to the United States. Injunctions in civil cases may be incredibly broad and may, for instance, prohibit operating a return preparation business—even indirectly. Although injunctions are equitable in nature, failure to comply may result in contempt sanctions—civil or criminal.

• Summons Enforcement.

If a taxpayer or third-party refuses to comply with an IRS summons during an audit or investigation, the government may petition the District Court to compel compliance. Conversely, taxpayers may challenge enforcement by moving to quash the summons. These cases often involve arguments over relevance, burden, and procedural issues. A taxpayer may potentially, for instance, lodge arguments that the summons seeks records that are not relevant or that are protected by a privilege.

• Bankruptcy Proceedings.

In bankruptcy, tax liabilities may become an issue as the IRS asserts claims against the estate. Disputes may arise over the priority, dischargeability, or amount of the IRS’s claim. These disputes may proceed like other federal civil litigation, with full discovery, motion practice, and evidentiary hearings as needed.

• Refund Suits.

If a taxpayer believes they have overpaid tax, they may file a refund suit—but only after full payment and exhaustion of administrative remedies. These cases are conducted de novo, meaning the court gives no deference to the IRS’s prior administrative determinations. Refund suits may involve disputes over the applicability of tax credits or deductions. For instance, a taxpayer might argue the United States owes them a refund because the IRS erroneously denied the taxpayer’s attempt to use a particular tax credit. In district court, the parties in that example would litigate the technical requirements of the credit and whether the credit applies to the facts at hand.

B. Criminal Tax Matters in District Court

Unlike civil matters, criminal tax cases are always prosecuted by the government and never initiated by a private party. They are tried exclusively in federal District Court. The charges may arise from a grand jury indictment, and they often carry significant penalties, including imprisonment, fines, restitution, and reputational harm.

Common charges include:

• Tax Evasion (26 U.S.C. § 7201).

Evasion requires a willful attempt to evade or defeat any tax. It comes in two forms: evasion of assessment (e.g., concealing income or inflating deductions) and evasion of payment (e.g., hiding assets or diverting income after the tax is assessed).

• Aiding and Assisting in the Filing of False Returns (26 U.S.C. § 7206(2))

This offense targets those who assist in the preparation or filing of materially false tax returns—for instance, that might include return preparers, accountants, and promoters.

• Willful Failure to Pay Over Trust Fund Taxes (26 U.S.C. § 7202).

Responsible persons who collect but fail to remit employment taxes may face felony charges if the failure was willful. The government often targets business owners or payroll officers in these cases.

• Willful Failure to File a Return (26 U.S.C. § 7203).

This misdemeanor applies when a taxpayer knowingly fails to file a required return. While the maximum sentence is one year per count, such charges are often used strategically to encourage compliance or to bolster more serious charges.

• Conspiracy to Defraud the United States (18 U.S.C. § 371).

This “crime of agreement” involves two or more persons conspiring to impair or obstruct the lawful function of the IRS. It is broader than traditional tax crimes and may encompass wide-ranging conduct, including deceptive schemes, false filings, and coordinated evasion. The government might charge multiple individuals or businesses under this statute in an attempt to convict actors whom the government believes coordinated together to engage in sort some of criminal tax fraud. The “agreement” is the crime; thus, the government usually takes the position that it need not prove the defendants ever carried out all the details of the “agreement.”

• False Statements (18 U.S.C. § 1001).

This statute criminalizes knowingly, materially false statements made to the federal government, including oral and written misrepresentations made to the IRS during audits or criminal investigations, in addition to other contexts.

C. Key Differences Between Civil and Criminal Tax Cases

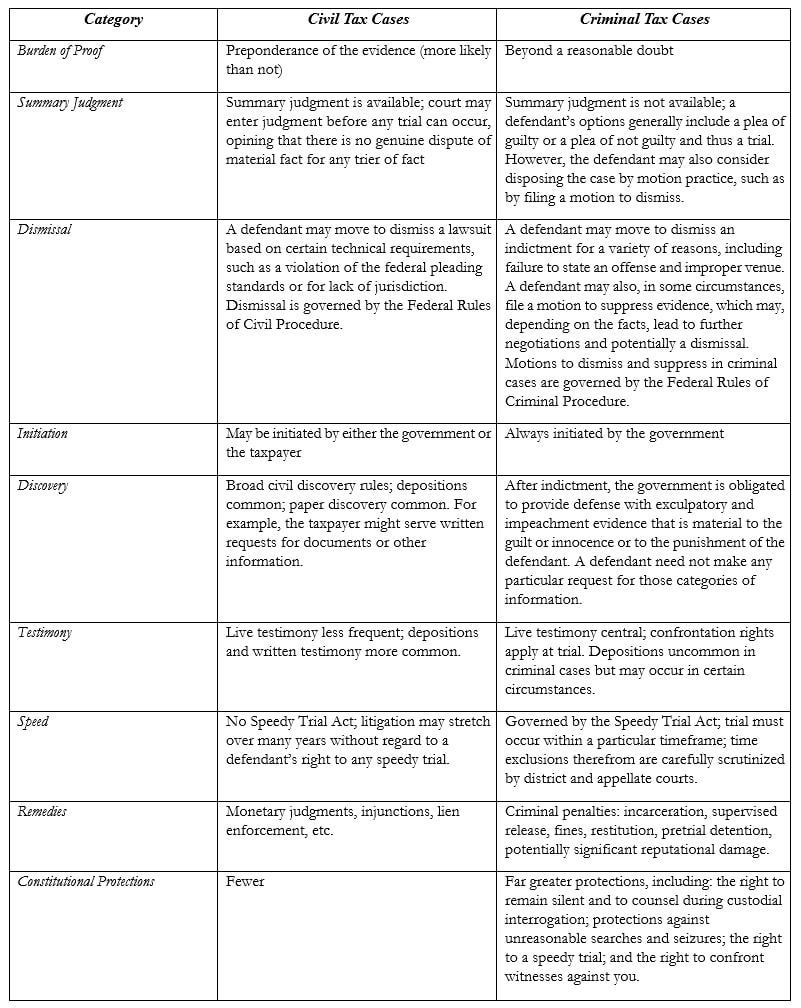

Understanding the distinction between civil and criminal tax cases requires more than just knowing the forum or the penalties involved. These are fundamentally different systems of justice with different governing rules. This is especially important because it is common for a civil case to implicate criminal tax issues, so knowing which rules and procedures apply—and which civil cases may potentially evolve into criminal matters—is critical. Generally, repeated alleged tax violations have a higher likelihood of becoming criminally prosecuted because the government may find it easier to prove the tax violation occurred “willfully” and beyond a reasonable doubt. However, other factors might also influence the government’s decision to seek a criminal indictment, such as the amount of “tax loss” at issue in the case or the sophistication of the alleged defendant.

The chart below summarizes some of the key differences between civil tax cases and criminal tax cases in district court:

Conclusion

Federal District Court plays a vital role in the enforcement and adjudication of federal tax laws. Whether the matter is civil or criminal, these courts handle some of the government’s most significant and complex tax cases. For civil litigants, the stakes often revolve around dollars and assets; for criminal defendants, liberty itself may hang in the balance. Understanding the distinct legal frameworks and procedures that govern these two tracks is critical to effective advocacy and to safeguarding a taxpayer’s rights at every stage.

If you have any questions regarding this blog post or any civil or criminal tax matter or any white collar criminal matter, you may contact me at emendoza@meadowscollier.com or by calling 214.749.2420.