March Tax Blog

March Tax Decisions

The Sixth Circuit holds that an IRS notice including certain employee-benefit plans with cash-value life insurance policies was invalid in Mann Constr., Inc. v. United States, No. 21-1500 (6th Cir. March 3, 2022).

The Sixth Circuit reversed a federal district court in holding that the issuance of a 2007 notice including certain employee-benefit plans featuring cash-value life insurance policies as listed transactions was invalid because the IRS did not provide notice or the opportunity for comment on the notice. Core to the analysis was Section 6707A of the Internal Revenue Code. This section permits the IRS to penalize the failure to provide information concerning “reportable” and “listed” transactions. Since the enactment of this section, the IRS has issued notices to identify these types of transactions. Typically, the IRS interprets statutes through regulations, which are in force after notice and comment, rather than notices, which do not require public notice and comment procedures.

At issue in the case was the taxpayer’s failure to report transactions related to an employee-benefit plan that was enumerated in an IRS notice in 2007. The IRS assessed penalties under Section 6707A, and the taxpayer instituted a refund suit in district court—alleging that the IRS should have provided public notice and comment on the 2007 notice under the Administrative Procedures Act. The IRS argued that it was not required to issue the rule after notice and comment, or Congress had removed the IRS from normal notice and comment requirements under the APA for issues related to tax shelters. The district court agreed with the IRS on the latter.

The Sixth Circuit reversed the district court. It held against the IRS on the first argument—agreeing with the district court. However, the Sixth Circuit held against the IRS on the second argument as well.

The Notice has the force and effect of law. It defines a set of transactions that taxpayers must report, and that duty did not arise from a statute or a notice-and-comment rule . . . Taxpayers like Mann Construction had no obligation to provide information regarding listed transactions like this one to the IRS before the Notice. They have such a duty after the Notice. Obeying these new duties can “involve significant time and expense,” and failure to comply comes with the risk of penalties and criminal sanctions, all characteristics of legislative rules.

In the Sixth Circuit’s opinion, Congress did not except the IRS from notice and comment rulemaking like this under Section 6707A.

The statutes merely establish a disclosure and penalty regime for the IRS to administer. As to the statutory text, Congress did not change the background procedural requirements of the APA or otherwise indicate an exemption from those requirements in a “clear” or “plain” way that would make the APA’s procedures inapplicable to the IRS. See Lockhart, 546 U.S. at 145–46.

This case is an interesting development for taxpayers in this context. It appears that federal appeals courts have taken notice of the IRS’ failure to follow normal rulemaking procedures in the context of reportable or listed transactions. This is a hot topic amongst courts currently, and there is a possibility that other courts may follow or disagree. But also of note is that this case was decided in the context of a refund suit. This may open a new avenue for taxpayers to argue against these penalties absent a proper notice and comment rule interpreting Section 6707A for the year at issue.

The Fifth Circuit holds that butane is not eligible for an alternative fuel tax credit under Section 6426(e) in Vitol, Inc. v. United States, No. 20-20237 (5th Cir. March 23, 2022)

In a case of first impression in the Fifth Circuit, the court analyzed whether butane is a liquified petroleum gas under section 6426(d)(2) of the Internal Revenue Code. Section 6426(e) provides a tax credit for use of any “alternative fuel” in producing any “alternative fuel mixture” for sale or use in a trade or business of the taxpayer. Under the statute, an “alternative fuel mixture” is a mixture of alternative fuel and taxable fuel. The definition of alternative fuel is provided in section 6426(d)(2), “[f]or purposes of this section, the term ‘alternative fuel’ means . . . liquefied petroleum gas.” The term taxable fuel is defined in Section 4083(a)(1) as gasoline, diesel fuel, and kerosene.

The taxpayer in Vitol, Inc. instituted a refund suit to recover the $8.8 million tax credit disallowed by the IRS. The taxpayer claimed that the IRS should have allowed a tax credit under 26 U.S.C. § 6426(e) for fuel blended with butane, a product Vitol introduced in 2013. Vitol argued that butane is a “liquefied petroleum gas” under § 6426(d)(2) and therefore an “alternative fuel” eligible for the § 6426(e) credit when mixed with a “taxable fuel.” The United States argued that butane is a “taxable fuel” and therefore not an eligible “alternative fuel.”

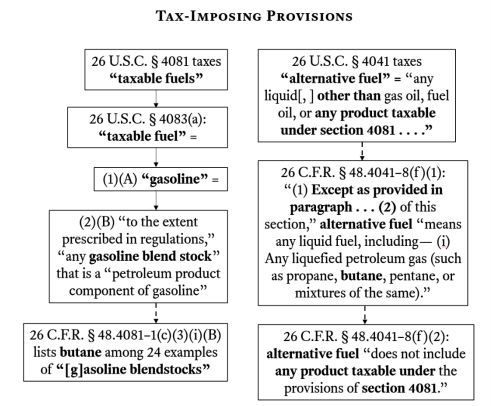

The Fifth Circuit first analyzed the statutory framework to determine if the terms were mutually exclusive. The court provided a helpful flowchart of the statutory framework for excise taxes on different types fuels.

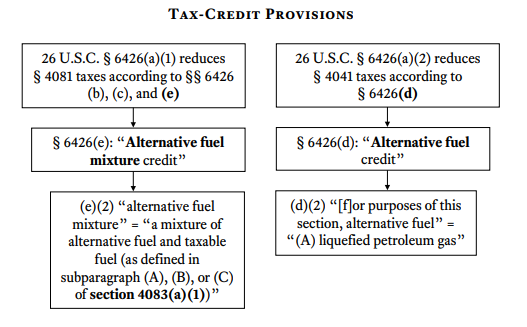

But the court also noted that the Internal Revenue Code provides tax credits for these taxes if fuel is made from certain components, as discussed above. Specifically, the Section 4041 tax for alternative fuel can be reduced by the alternative fuel credit at Section 6426(d). The Section 4081 tax for taxable fuel can be reduced by the alternative fuel mixture credit at Section 6426(e), for fuel that is “a mixture of alternative fuel and taxable fuel.” The court again provided a useful flowchart for these provisions.

At issue in the case was whether butane is excluded from the definition of an LPG under Section 6462(d)(2). The Fifth Circuit held that plain language of the statute excepted butane from the definition—holding against the taxpayer.

Although the common meaning of LPG includes butane, § 6426(d)(2) is a subsidiary part of a broader statutory framework that treats a given fuel as either a taxable fuel or an alternative fuel, but not both. Section 6426 separates taxable fuels and alternative fuels using two distinct subparts. And in those subparts, § 6426 expressly references the structural relationships between its credits and the taxes they offset, imposed at § 4081 and § 4041. And those provisions, in turn, define alternative fuels to exclude any taxable fuel. Thus, the statutory framework is mutually exclusive: A given fuel is either taxable or alternative, but not both. The statutory context of § 6426 provides sound reason to depart from butane’s common meaning.

The Fifth Circuit noted that Section 4083 defines butane as a taxable fuel. And given that butane is a taxable fuel, the plain language of the tax credit provisions makes it clear that a fuel cannot both be a taxable fuel and an alternative fuel, which butane arguably is since it is also an LPG—an alternative fuel. The Fifth Circuit states that the ordinary meaning generally controls, which would mean that butane is an LPG, and, therefore, it is an alternative fuel. However, the Fifth Circuit analyzed the statutory text or context to determine if the ordinary meaning is correct. The court held that the context demonstrates that a fuel cannot be both a taxable fuel and an alternative fuel because of how the credits only reduce one specific excise tax—indicating that taxable fuels and alternative fuels must be sectioned off from one another. In other words, “[f]or there to be a § 6426 credit, there must first be a § 4081 or § 4041 tax. And those provisions leave no doubt that a given fuel is excluded from the tax regime for alternative fuels if it qualifies as a taxable fuel.” Taxpayers in the oil and gas industry should take note of this interesting opinion, which is a rarely-seen case analyzing these fuel tax credit provisions.

Fifth Circuit upholds the exclusion of “other act” evidence in a tax fraud case in United States v. Williams et. al., No. 22-30007; No. 22-30008 (5th Cir. March 29, 2022).

In this case, a federal grand jury indicted an attorney for lying on his taxes and failing to report large cash transactions to the IRS. Specifically, the indictment charged an attorney and his law partner with conspiring to defraud the United States in 2011-2019 by filing false tax returns and failing to report cash payments over $10,000. In addition, they were charged with aiding or assisting tax fraud from 2013-2017. The alleged conspiracy included working with a tax preparer to inflate Schedule C business expenses, reducing the attorney’s taxes by $200,000. It also included amending earlier returns prior to the conspiracy to reduce already existing tax debt. The government sought to admit evidence of the attorney’s tax history from the years predating the charged conduct. The district court excluded such evidence, and the Fifth Circuit affirmed the district court’s exclusion of evidence.

At issue was whether the evidence was improper “other act” evidence under Rule 404(b) and, alternatively, inadmissible under the Rule 403 balancing test. Before trial was set to begin, the government filed a notice of intent to introduce “other acts” evidence. The notice sought to introduce testimony and documents about the attorney’s “handling of his income taxes prior to the tax years charged in the indictment.” According to the government, the evidence showed that starting in 2002, Williams filed and paid his taxes late. His recurrent tardiness resulted in IRS debt and liens, some of which existed when the conspiracy began in 2011. The government also wanted to show that Williams “had conversations with the IRS about these tax issues.” These tax issues, the government argued, showed his intent to commit tax fraud.

The district court allowed the government to introduce limited evidence about the attorney’s tax history to the extent that it was necessary to explain how the conspiracy began. It also allowed evidence about the attorney improperly deducting his overdue tax payments as business expenses during the years the government charged him. However, the district court excluded the rest of the attorney’s tax history predating the conspiracy, which included evidence of late filings, payments, and correspondence with the IRS. It reasoned that the evidence is “classic propensity evidence,” probative only of Williams’s propensity to cheat the IRS, and thus barred by Rule 404(b)(1). But the district court gave the government the benefit of the doubt, assuming that the evidence is “marginally probative of Williams’s willfulness to commit tax fraud.” But despite this, the court ruled that the evidence would be prejudicial and would substantially outweigh probative value. However, the district court also left some room to change its opinion by providing that “evidence at trial may change the complexion of what informs [its] rulings.”

The Fifth Circuit affirmed the district court. However, the court noted that is review of the district court’s decision was “impaired” because its review “takes place without knowledge of the evidence or arguments on which trail will turn.” Nonetheless, the court analyzed Federal Rule of Evidence 404. That rule prohibits using evidence of “any other crime, wrong, or act” to “prove a person’s character in order to show that on a particular occasion the person acted in accordance with the character.” It does, however, allow using other-act evidence for “another purpose, such as proving motive, opportunity, intent, preparation, plan, knowledge, identity, absence of mistake, or lack of accident.” But evidence under this rule must still pass the Rule 403 balancing test, which excludes evidence when “its probative value [for a permissible use] is substantially outweighed by a danger of one or more of the following: unfair prejudice, confusing the issues, misleading the jury, undue delay, wasting time, or needlessly presenting cumulative evidence.” The Fifth Circuit believed that the attorney’s tax history may well be admitted under Rule 404(b) to prove intent or knowledge of tax obligations. But the Fifth Circuit agreed that the district court did not abuse its discretion in excluding the evidence under Rule 403:

The probative value of [the attorney’s] tax history for any permissible use does not seem high. Other acts are more probative of intent when they are similar to the charged acts . . . Paying taxes late is not the same as lying on tax forms. And although [the attorney’s] tax delinquencies and communications with the IRS might show his familiarity with how taxes work in general, they say little about his knowledge of Schedule C business expenses. In contrast, the district court identified substantial risks from admitting [the attorney’s] tax history. Admitting the evidence gives the jury the chance to decide the case on an improper basis: [the attorney] is guilty because he is the type of person who doesn’t follow the tax laws. This concern is “particularly great” when, as here, the other acts have gone unpunished. On top of this, risks of confusion and delay abound. The exhibits the government seeks to introduce span close to a decade, raising the strong possibility of minitrials over late filings and civil IRS disputes that might distract the jury from the charged conduct.

This case is a good outline of how courts analyze “other act” evidence in the context of fraud cases. Courts are careful to admit evidence of previous acts in this context if they are not similar to the charged acts in the indictment. Even if such evidence is permissible under one rule, taxpayers may be afforded relief under the Rule 403 balancing test.

Another court deals a blow to non-willful FBAR violators, non-willful FBAR penalties are charged on a per-account basis in United States v. Hadley, No. 8:21-cv-01357 (M.D. Fla., March 28, 2022).

In my blog post covering November 2021 tax opinions, I discussed the Fifth Circuit opinion in United States v. Bittner, No. 20-40597 (5th Cir.), which held that non-willful FBAR penalties applied on a “per account” basis. As noted in that post, there is now a circuit split on whether non-willful FBAR penalties are applied on a “per account” or “per form” basis. See e.g., United States v. Boyd, 991 F.3d 1077 (9th Cir. 2021). The Middle District of Florida issued an opinion following in the steps of the Fifth Circuit:

The term "violation" in 31 U.S.C. § 5321(a)(5)(A) is not the procedural failure to file an FBAR form. See United States v. Jan Stromme, No. 1:20-cv-24800-UU (S.D. Fla. January 25, 2021) (Doc. 18, p. 3) ("[E]ach unreported relationship with a foreign financial agency constitutes an FBAR violation."). Instead, under the statutory duty imposed in Section 5314 and the implementing regulations, the meaning of the term "violation" is failing to report each foreign financial account relationship. The complaint alleges Ms. Hadley committed twenty-three such "violations," thus authorizing the government’s imposition of $230,000 in total penalties.

Notably, the court briefly mentioned other courts’ decisions to the contrary in a footnote, “[t]he court acknowledges there is contrary authority on this issue. See United States v. Boyd, 991 F.3d 1077, 1085 (9th Cir. 2021); United States v. Kaufman, 3:18-CV-00787 (KAD), 2021 WL 83478, **8-11 (D. Conn. Jan. 11, 2021); United States v. Giraldi, CV202830SDWLDW, 2021 WL 1016215, *5 n.8 (D.N.J. Mar. 16, 2021).” This case continues to underscore the growing divide amongst courts on this issue, as courts are beginning to acknowledge authority to the contrary. Thus, this issue is ripe for consideration by the Supreme Court in the near future.

***

For any questions about these decisions or any other criminal or civil tax-related matters, please feel free to contact Ryan Dean at (214)749-2430 or rdean@meadowscollier.com.